On the Origins of The SOLID Principles

(19 mins reading time)

Since school, I've always tried to dig out the history and the back-scenes behind the physics principles so I can grasp the foundations of them. Even now, while I'm in the software field, I'm always curious about how those famous figures come up with such technologies, principles and ideas. And for this episode of my blog show, It's going to be the infamous S.O.L.I.D.

SOLID principles are one of the most famous principles among software engineers for writing clean code, although most of my time that I spend coding, I totally forget about that they exist, I'm pretty sure that most of us apply them one way or another without explicitly thinking about them.

Parts of this article was intended for training sessions we are currently conducting internally at my workplace, most of the simplified examples presented here are from my personal experience, and since it has some back-scenes on where do those principles originate from -which I didn't find on many many dev blogs- I've decided to publish it.

SOLID is an acronym for 5 design principles (coding principles). Those principles are intended mainly for OOP paradigm. They were introduced by Robert Martin in his 2000 paper: Design Principles & Design Patterns. In the paper, Robert actually didn't only specify 5 principles... there are more, but the SOLID are the most famous ones.

- Single Responsibility principle.

- Open-Closed principle.

- Liskov substitution principle.

- Interface Segregation principle.

- Dependency Inversion principle.

The Ugly Truth

What goes wrong with software? The design of many software applications begins as a vital image in the minds of its designers. At this stage it is clean, elegant, and compelling. It has a simple beauty that makes the designers and implementers itch to see it working. Some of these applications manage to maintain this purity of design through the initial development and into the first release.

But then something begins to happen. The software starts to rot. At first it isn’t so bad. An ugly wart here, a clumsy hack there, but the beauty of the design still shows through. Yet, over time as the rotting continues, the ugly festering sores and boils accumulate until they dominate the design of the application. The program becomes a festering mass of code that the developers find increasingly hard to maintain. Eventually the sheer effort required to make even the simplest of changes to the application becomes so high that the engineers and front line managers cry for a redesign project.

Such redesigns rarely succeed. Though the designers start out with good intentions, they find that they are shooting at a moving target. The old system continues to evolve and change, and the new design must keep up. The warts and ulcers accumulate in the new design before it ever makes it to its first release. On that fateful day, usually much later than planned, the morass of problems in the new design may be so bad that the designers are already crying for another redesign.

Symptoms of rotten software

There are four primary symptoms that tell us that our designs are rotting. They are not orthogonal, but are related to each other in ways that will become obvious. they are: rigidity, fragility, immobility, and viscosity.

Rigidity

Rigidity is the tendency for software to be difficult to change, even in simple ways. Every change causes a cascade of subsequent changes in dependent modules. What begins as a simple two day change to one module grows into a multi-week marathon of change in module after module as the engineers chase the thread of the change through the application.

When software behaves this way, managers fear to allow engineers to fix non-critical problems. This reluctance derives from the fact that they don’t know, with any reliability, when the engineers will be finished. If the managers turn the engineers loose on such problems, they may disappear for long periods of time. The software design begins to take on some characteristics of a roach motel -- engineers check in, but they don’t check out.

When the manager’s fears become so acute that they refuse to allow changes to software, official rigidity sets in. Thus, what starts as a design deficiency, winds up being adverse management policy.

Fragility

Closely related to rigidity is fragility. Fragility is the tendency of the software to break in many places every time it is changed. Often the breakage occurs in areas that have no conceptual relationship with the area that was changed. Such errors fill the hearts of managers with foreboding. Every time they authorize a fix, they fear that the software will break in some unexpected way.

As the fragility becomes worse, the probability of breakage increases with time. Such software is impossible to maintain. Every fix makes it worse, introducing more problems than are solved.

Such software causes managers and customers to suspect that the developers have lost control of their software. Distrust reigns, and credibility is lost.

Immobility

Immobility is the inability to reuse software from other projects or from parts of the same project. It often happens that one engineer will discover that he needs a module that is similar to one that another engineer wrote. However, it also often happens that the module in question has too much baggage that it depends upon. After much work, the engineers discover that the work and risk required to separate the desirable parts of the software from the undesirable parts are too great to tolerate. And so the software is simply rewritten instead of reused.

Viscosity

Viscosity comes in two forms: viscosity of the design, and viscosity of the environment. When faced with a change, engineers usually find more than one way to make the change. Some of the ways preserve the design, others do not (i.e. they are hacks.) When the design preserving methods are harder to employ than the hacks, then the viscosity of the design is high. It is easy to do the wrong thing, but hard to do the right thing.

Viscosity of environment comes about when the development environment is slow and inefficient. For example, if compile times are very long, engineers will be tempted to make changes that don’t force large recompiles, even though those changes are not optimal from a design point of view. If the source code control system requires hours to check in just a few files, then engineers will be tempted to make changes that require as few check-ins as possible, regardless of whether the design is preserved.

These four symptoms are the tell-tale signs of poor architecture. Any application that exhibits them is suffering from a design that is rotting from the inside out. But what causes that rot to take place?

Changing Requirements

The immediate cause of the degradation of the design is well understood. The requirements have been changing in ways that the initial design did not anticipate. Often these changes need to be made quickly, and may be made by engineers who are not familiar with the original design philosophy. So, though the change to the design works, it somehow violates the original design. Bit by bit, as the changes continue to pour in, these violations accumulate until malignancy sets in.

However, we cannot blame the drifting of the requirements for the degradation of the design. We, as software engineers, know full well that requirements change. Indeed, most of us realize that the requirements document is the most volatile document in the project. If our designs are failing due to the constant rain of changing requirements, it is our designs that are at fault. We must somehow find a way to make our designs resilient to such changes and protect them from rotting.

Dependency Management

What kind of changes cause designs to rot? Changes that introduce new and unplanned implementations to dependencies. Each of the four symptoms mentioned above is either directly, or indirectly caused by improper dependencies between the modules of the software. It is the dependency architecture that is degrading, and with it the ability of the software to be maintained.

In order to forestall the degradation of the dependency architecture, the dependencies between modules in an application must be managed. This management consists of the creation of dependency firewalls.A cross such firewalls, dependencies do not propogate.

Object Oriented Design is replete with principles and techniques for building such firewalls, and for managing module dependencies.

Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

A class should have only a single responsibility, that is, only changes to one part of the software's specification should be able to affect the specification of the class.

What does this mean ?

Imagine a typical business organization. There is a CEO at the top. Reporting to that CEO are the C-level executives: the CFO, COO, and CTO among others. The CFO is responsible for controlling the finances of the company. The COO is responsible for managing the operations of the company. And the CTO is responsible for the technology infrastructure and development within the company.

Now consider this bit of Java code:

public class Employee {

/* Employee properties

public String Name;

public String Address;

... etc */

public Money calculatePay();

public void save();

public String reportHours();

}

The calculatePay method implements the algorithms that determine how much a particular employee should be paid, based on that employee’s contract, status, hours worked, etc.

The save method stores the data managed by the Employee object onto the enterprise database.

The reportHours method returns a string which is appended to a report that auditors use to ensure that employees are working the appropriate number of hours and are being paid the appropriate compensation.

Now, which of those C-Level executives reporting to the CEO is responsible for specifying the behavior of the calculatePay method? Which of them would be fired[1] by the CEO if that method were catastrophically mis-specified? Clearly the answer is the CFO. Specifying the pay of employees is a financial responsibility. If all the employees were paid double for a year because someone in the CFOs organization mis-specified the rules for calculating pay, the CFO would likely be fired.

A different C-Level executive is responsible for specifying the format and content of the string returned from the reportHours method. That executive manages the auditors and reviewers, and that’s an operations responsibility. So if there were a catastrophic mis-specification of that report, the COO would be fired.

Finally, it should be obvious which of the C-Level executives would be fired if there were a catastrophic mis-specification of the save method. If the enterprise database were to be corrupted by such a horrific mis-specification, the CTO would likely be fired.

So it stands to reason that when changes are made to the algorithm within the calculatePay method, the request for those changes will originate from the organization headed by the CFO. Similarly it will be the COO’s organization that will request changes to the reportHours method, and the CTOs organization that will request changes to the save method.

And this gets to the crux of the Single Responsibility Principle. This principle is about people.

When you write a software module, you want to make sure that when changes are requested, those changes can only originate from a single person, or rather, a single tightly coupled group of people representing a single narrowly defined business function. You want to isolate your modules from the complexities of the organization as a whole, and design your systems such that each module is responsible (responds to) the needs of just that one business function.

Why? Because we don’t want to get the COO fired because we made a change requested by the CTO. Nothing terrifies our customers and managers more that discovering that a program malfunctioned in a way that was, from their point of view, completely unrelated to the changes they requested. If you change the calculatePay method, and inadvertently break the reportHours method; then the COO will start demanding that you never change the calculatePay method again.

Imagine you took your car to a mechanic in order to fix a broken electric window. He calls you the next day saying it’s all fixed. When you pick up your car, you find the window works fine; but the car won’t start. It’s not likely you will return to that mechanic because he’s clearly an idiot.

The problem with the previous example is that the Employee class has three responsibilities: 1- defining Employee properties and data persistence. 2- defining the pay slip logic 3- defining the work hours logic.

To make the class adhere to the Single Responsibility Principle, we will extract the logic from the Employee class and create two separate classes that are responsible for pay slip and work hours logic.

public class Employee {

/* Employee properties

public String Name;

public String Address;

... etc */

public void save();

}

public class PaySlipService {

public Money calculatePay(Employee employee);

}

public class WorkHoursService {

public String reportHours(Employee employee);

}

Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

A module should be open for extension but closed for modification.

It means simply this: We should write our modules so that they can be extended, without requiring them to be modified. In other words, we want to be able to change what the modules do, without changing the source code of the modules.

This may sound contradictory, but there are several techniques for achieving the OCP on a large scale.

For instance, let's suppose we're developing an HR system which keeps track of the employees directory and calculates their pay slip based on their contract type. For example Part-Time contract and Full-Time contract. The design of such system without taking in consideration the OCP would be:

public class Employee {

/* Employee properties */

public String type;

public double calculatePaySlipForPartTime();

public double calculatePaySlipForFullTime();

}

And when using the Employee class, programmers would make the code littered with if/else or switch statement. Every time anything needs to be done to the employee, a switch statement if/else chain will need to select the proper functions to use. When new type of employees are added, or payslip policy changes, the code must be scanned for all these selection statements, and each must be appropriately modified.

public double getPaySlip(Employee employee){

if(employee.type == "Part-Time")

return employee.calculatePaySlipForPartTime();

else

return employee.calculatePaySlipForFullTime();

}

Such structures make the system much harder to maintain, and are very prone to error. Now, in case we need to add a new type of employees, for example One-Time-Only, we would have to change the code in two places: the Employee class and the class that has the function getPaySlip. To rethink of the design of such a case, the solution would be fisible through Polymorphism. It would be:

public abstract class Employee {

/* Employee properties */

public virtual double calculatePaySlip();

}

public class PartTimeEmployee extends Employee {

public double calculatePaySlip(){

/* logic for part time employee */

}

}

public class FullTimeEmployee extends Employee {

public double calculatePaySlip(){

/* logic for full time employee */

}

}

And when calling the pay slip logic, regardless of the employee type :

public double getPaySlip(Employee employee){

return employee.getPaySlip();

}

Now, when we're going to add a new type of an employee, we won't be making any modification to the existing code. not the Employee class and not the remaining logic of getting the pay slip. We would only need to define a new class of OneTimeOnlyEmployee and implements its corresponding logic.

REMEMBER: calculating employee pay slip should not be the responsibility of Employee class due to SRP.

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

Subclasses should be substitutable for their base classes.

In Head First OOA&D. They present a scenario where you are a developer on a project to build a framework for strategy games.

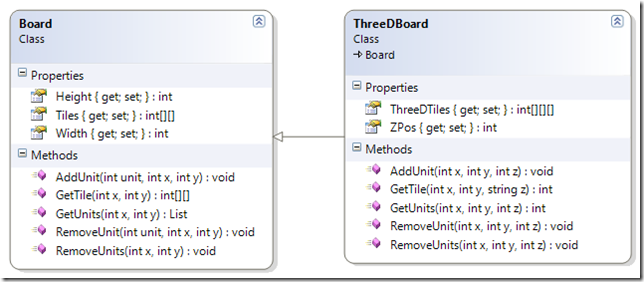

They present a class that represents a board that looks like this:

All of the methods take X and Y coordinates as parameters to locate the tile position in the two-dimensional array of Tiles. This will allow a game developer to manage units in the board during the course of the game.

The book goes on to change the requirements to say that the game frame work must also support 3D game boards to accommodate games that have flight. So a ThreeDBoard class is introduced that extends Board.

At first glance this seems like a good decision. Board provides both the Height and Width properties and ThreeDBoard provides the Z axis.

Where it breaks down is when you look at all the other members inherited from Board. The methods for AddUnit, GetTile, GetUnits and so on, all take both X and Y parameters in the Board class but the ThreeDBoard needs a Z parameter as well.

So you must implement those methods again with a Z parameter. The Z parameter has no context to the Board class and the inherited methods from the Board class lose their meaning. A unit of code attempting to use the ThreeDBoard class as its base class Board would be very out of luck.

Maybe we should find another approach. Instead of extending Board, ThreeDBoard should be composed of Board objects. One Board object per unit of the Z axis.

This allows us to use good object oriented principles like encapsulation and reuse and doesn’t violate LSP.

Thanks NotMySelf for the nice example.

Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

Many client specific interfaces are better than one general purpose interface

Simply, this principle states that no clients (interface implementers) should implement methods that they don't use. Usually programmers implements those mthods as dummy methods with empty logic. This symptom in the code is called Interface Pollution or Fat Interfaces. These practices harm code readibility and maintainability.

REMEMBER: the difference between an interface and a class is that interfaces defines behaviour only, while classes mostly define properties and attributes.

Suppose we're developing an accounting system, and we're defining our model with an Invoice class and Bill class. Those two entities should generate journal entries and a transaction history, so the could can be:

public interface ITransactional {

void generateJournalEntry();

void generateTransactionHistory();

}

public class Invoice implements ITransactional {

public void generateJournalEntry(){

/* some logic */

};

public void generateTransactionHistory(){

/* some logic */

}

}

public class Bill implements ITransactional {

public void generateJournalEntry(){

/* some logic */

};

public void generateTransactionHistory(){

/* some logic */

}

}

Now, suppose that we're adding to our model an entity for PurchaseOrder. This entity doesn't generate a journal entry. so in our case the code for the PurchaseOrder class would be:

public class PurchaseOrder implements ITransactional {

public void generateJournalEntry(){

/* DUMMY LOGIC GOES HERE */

};

public void generateTransactionHistory(){

/* some logic */

}

}

Making the PurchaseOrder an ITransaction makes our application treats the PurchaseOrder as an ITransaction in some places where invoked, and when the dummy code is used it might be invoked in places where it might break the application.

Adhering to the Interface Segregation Principle would force us to split the interface ITransaction into two interfaces like below:

public interface ITransactional {

void generateTransationHistory();

}

public interface IJEGenerator {

void generateJournalEntry();

}

In other words, interfaces shouldn’t include too many functionalities.

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Depend upon Abstractions. Do not depend upon concretions.

Suppose we have a controller class that should use some logging mechanism. If I'm tasked with establishing a quick logging mechanism in a such controller, I'm might go with a file logger (log into a file). For example:

public class Controller extends WebController {

private FileLogger logger;

public Controller(){

logger = new FileLogger();

}

public String GetData(){

try {

//... some logic

}catch(Exception e){

logger.log(e);

}

}

}

And as I'm standing at the coffee machine, I think about the poor soul who is going to edit the whole code base when we might need to log into a database, so I rush back into my pc and refactor the code to the following:

public class Controller extends WebController {

private ILogger logger;

public Controller(ILogger logger){

this.logger = logger;

}

public String GetData(){

try {

//... some logic

}catch(Exception e){

logger.log(e);

}

}

}

The thing is, that at the first attempt, class Controller depends on FileLogger, so we refactored the code and created an interface ILogger which FileLogger implements. And we supply the Controller when instantiating one with the appropriate implementation, let it be FileLogger or DatabaseLogger for example. In this way the dependency on FileLogger has been inverted outside of the scope of Controller.

References

- Thanks to Ahmad Alkhous for helping out with the examples.

- Robert Martin's paper.

- Thanks to Derick Bailey and others for the nice images.

- And who ever blogged about SOLID.